A dog’s nervous system is divided into two sections; the Central Nervous System (brain and spinal cord) which controls the response to environmental stimulus and the Peripheral Nervous System which manages other, subconscious acts, including stress response.

We often perceive stress as a psychological response but the functions of the latter mean that we also need to be aware of the physical responses in the dog’s body and their repercussions on the long term health of the animal.

The Autonomic Nervous System, part of the Peripheral Nervous System, is responsible for involuntary responses.

It is divided into two sections:

Sympathetic Division

Controls the ‘fight or flight’ response which is critical to survival. When apparent danger is perceived, this system sends signals to the heart and other organs prompting them to prepare for a quick reaction of either retreat or defence. The body responds by providing the bloodstream with additional glucose for energy, producing adrenaline, redistributing blood flow and increasing lung capacity through bronchiole dilation.

Parasympathetic Division

Controls everyday subconscious organ functions such as breathing and heart rate. This system is also responsible for slowly reversing the effects of the Sympathetic Division when the perceived danger has passed.

Both systems function continuously, however their output either increases or regulates depending on the situation.

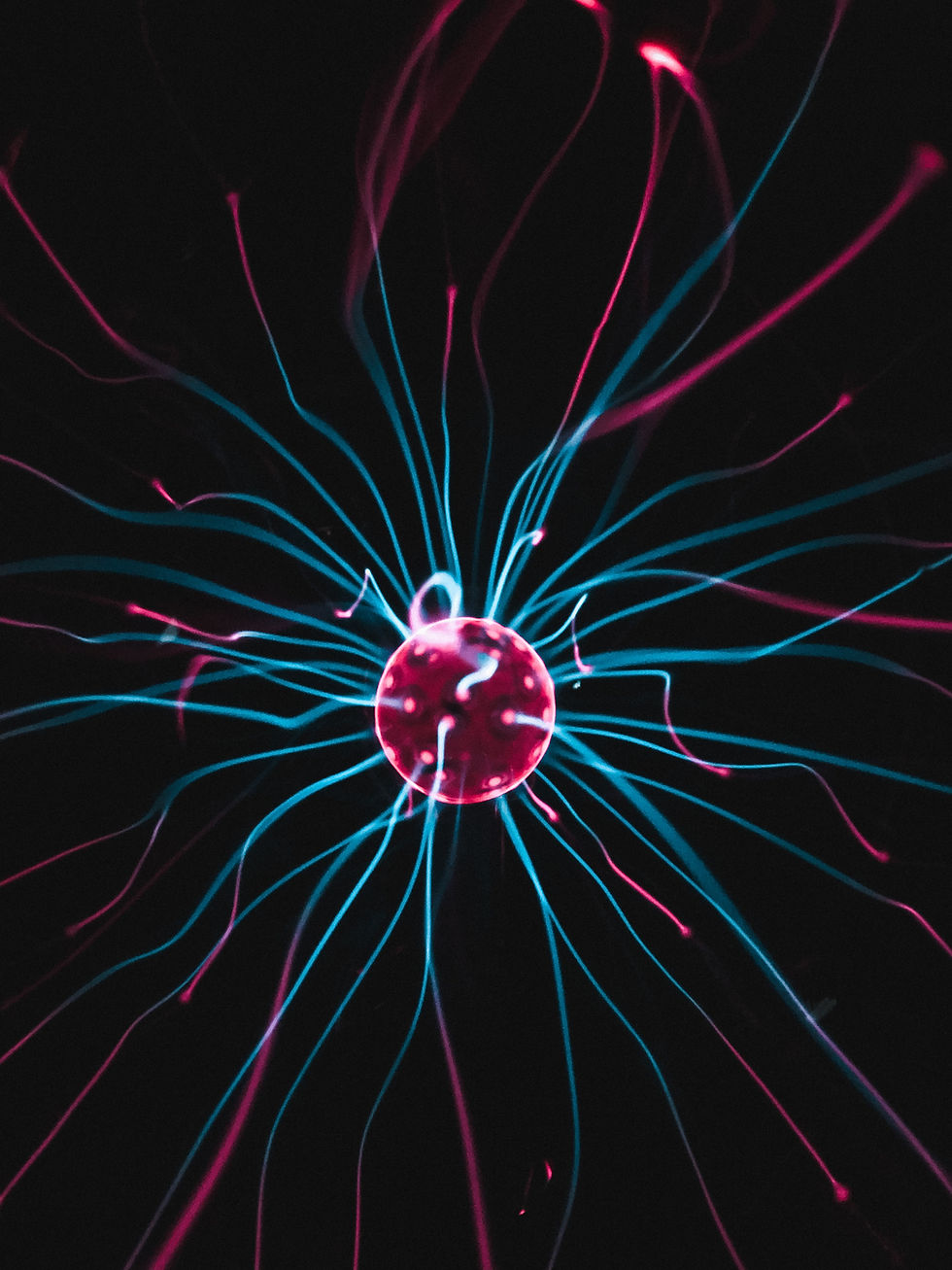

Communication between neurons in the dog's brain occurs through a neurotransmission process named Synapse. The Synapse speeds up or slows down when a neurotransmitter is released into the brain. The neurotransmitter which deals specifically with the body’s response to stress is called Noradrenaline, a chemical which is released from the ends of Sympathetic nerve fibres. Noradrenaline works by quickly stimulating the nervous system and ‘fight or flight' response, triggering the Cerebral Cortex to create mental states such as arousal and alertness.

When a dog is subjected to stress the Synapse speeds up, then slows down to reverse the effects and calm the animal when the trigger for the stress is removed. When a dog is subjected to a build-up of stress and the Synapse is unable to fully reverse the effects of each stressor before the next one occurs, this is known as ‘trigger stacking’.

When the dog's system goes into ‘fight or flight’ response, all of it’s energy is redirected towards the functions which provide immediate life-saving reactions. The immune system offers no assistance in this scenario and as a consequence is essentially switched off. The increase in emotion related hormones add further pressure to the system. The digestive system slows down since it is also of no assistance to the dog in either defending itself or running away. This means less nutrients can be absorbed into the body.

Signs your dog may be stressed include:

· Panting (when not hot)

· Yawning (when not tired)

· Licking their lips

· Turning their head to avoid eye contact, perhaps showing the whites of their eyes

· Dilated pupils

· Cowering

· Ears pinned down or back

· Tail tucked under

Stress can be temporary, for example a visit to the vet’s office, or it could be long term, for example a dog who is afraid of other dogs or people being walked in a busy park on a daily basis. When dogs are subjected to long term stress the body can never return to it’s full functionality, so the dog is left with compromised immunity and unable to defend itself from illness and infection. In addition because of their reduced digestive capacity, the body is not able to absorb all of the nutrients from the diet that they require to stay healthy.

A dog who is subjected to fear and stress on a regular basis is not only psychologically unhappy but is also likely to be physically unhealthy. As your dog’s guardian it is vital to protect them from enduring any undue stress by monitoring them for stress signals and avoiding, wherever possible, activities known to cause them stress. This will be unique to the individual dog and while some scenarios may be unavoidable, the trip to the vets for example, with positive reinforcement training and the guidance of a professional trainer or behaviourist, it may be possible to recondition your dog’s association with the experience from negative to positive, or at least neutral.

Comments